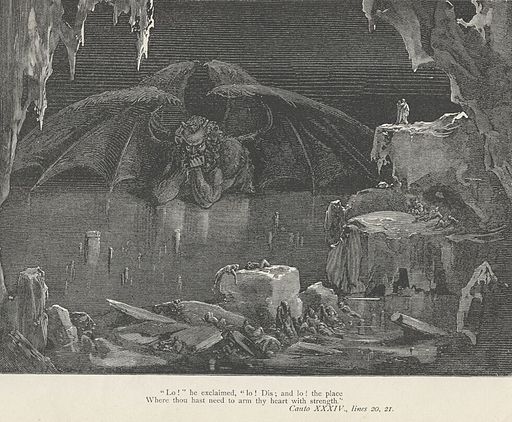

The gratefulness and thankfulness that is supposed to accompany this season is somewhat at odds with a culture that preaches one to be “proud” of one’s accomplishments or to take “pride” in their work. How often do we hear hear someone tell us to be “proud” of this or that, or even parents telling their children to be proud of some accomplishment? Pride is almost mistaken for a virtue – odd, since early understandings of the term placed it as, ultimately, the worst of the seven deadly sins. Dante even reserves the final encounter with Dis (Satan or Lucifer) in the 9th circle of hell as an encounter with the embodiment of pride.

Gustave Doré, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

While early religious based understandings and definitions of pride may not be exactly how the word is used today, I’m one who puts a lot into words and how they are used. So I ask, how did we, as a society, get here, to this different understanding of pride? Is this even an issue? Is pride really a problem, or is it a benefit to society instead? And, of course, what does it all mean for architecture?

First off, as I alluded to already, I admit that how the term “pride” is used today (as in the examples noted at the beginning of this post) likely is not intended to mean the same thing as how it is understood as a sin. More so, as often used today, it can simply mean a mere consciousness of one’s own dignity, rather than a gratuitous hubris or pleasure taken in ones own abilities or achievements. All things in moderation, right? Nonetheless, all manner of pride, if even in the most innocent sense, involves some level of self assertion. Self-assertion, in and of itself is not necessarily a problem, as an individual certainly needs to be able to have some strong belief and confidence in one’s self from time to time (though not exclusively one’s self). Pride, however, in a disordered view and world, allows that self-assertion to come from a perspective of “I alone” self assertion, not cognizant of the factors, parameters, and variables that also played into the perceived individual success or achievement.

Architects are notorious for this self assertion. So many so called “star-chitects” or celebrity/famous architects are known simply for a strong self assertion of their singular unique approach to design as if it is inherent to them and them alone, strongly tied to their name. How many people are working behind the scenes for the Gehrys, the Hadids, the Ramuses, or even the Rohes of the architecture world? We don’t know their names, it’s not about them, or so the message is made clear. Furthermore, not to denigrate any specific work of any of these star-chitects, I rather refer back to a point made by Miravalle in his book “Beauty: What It Is & Why It Matters” that I reviewed in a post earlier this month. In his review of beauty in architecture, he notes that every “human building is the imposition of art on a neighborhood, a street, or a community.” He then later asserts that “thus, when any building is an expression of simple self-assertion, it hurts the community.” He notes this occurs in worst form when designers engage in “raw disorder” or sole “whims of self-expression.”

Architecture itself has been a strong symbol of pride, even from the earliest days of history or pre-history. The story of the Tower of Babel is a good reminder of how closely we tie our buildings to our own sense of self-importance – in pure hubris, humanity attempted to play God and reach the heavens (and, ultimately was rebuked and scattered). David Cloutier in “Walking God’s Earth: The Environment and Catholic Faith” further remarks on the story of Babel:

“Scale is a spiritual problem that goes back to an inability to see beauty. It is so focused on its own grand ambitions that it fails to see not only the harm being caused but also the beauty of the order that actually exists and the need to work with that order.”

A more recent example of this Babel phenomenon is the Burj Khalifa in Dubai. As Miravalle points out, it’s hard not to think that size was the primary reason for building it. He also likens it to the quantity of houses built simply to be large – purely for affirmation of the owner or “shouting to the world about themselves.“

So what’s the point? Pride, in distracting us from the other elements contributing to our existing and built environments or community fabric, can lead us to ignore that context altogether and result in a chaotic landscape of egos and self-assertion that is arguably no longer beautiful.

Confession: I am proud. I’m proud of a lot of my projects. I’m proud of a number of posts I’ve written for this blog. I’m proud for having the courage to write about pride to an architecture audience – ha! We all experience pride. It is part of the human condition. So there is no easy “fix” to simply eradicate it, or even change the culture’s understanding of it, rather there is hope and merit for acknowledging it and understanding it, and why its good to constantly be in struggle against it. We probably can’t defeat it (not in this lifetime anyway), and we’ll always encounter those proud architects and “proud” buildings (not the British sense of the word we architects like to use, by the way). Rather, being conscious of how our own pride is, unintentionally, inserting itself into our designs and decisions as architects, designers, and builders can help create a more inclusive, enriching, and ultimately more beautiful built environment.

Feature image By Pieter Brueghel the Elder – bAGKOdJfvfAhYQ at Google Arts & Culture, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22178101

Chase Kramer, AIA, is the Director of Design for TSP Inc. in Sioux Falls. He received his M.Arch from ISU where he focused on urban design and sustainability. Before that, he received a degree in Art from Augustana University. He lives in Sioux Falls with his wife and four children. Beyond Architecture, he is an AI early adopter, musician, art lover, and fan of cheese and beer.